The Lectio Letter - Issue #98 - The Work we Worship that makes us Slaves

“This is why we believe in Jesus Christ—to help us see that we are not what we ought to be and to help us become what we ought to be.”

― Miroslav Volf, Exclusion and Embrace

“Whatever a Christian understanding of Vocation is, it is shaped by the first command to lay down our nets”

— (overheard somewhere ;)

“I no longer call you servants but friends”

— Jesus of Nazareth

“Sabbath, in the first instance, is not about worship. It is about work stoppage. It is about withdrawal from the anxiety system of Pharaoh, the refusal to let one’s life be defined by production and consumption and the endless pursuit of private well-being.”

― Walter Brueggemann

Welcome to Issue #98 of the Lectio Letter. This members-only newsletter is filled with music, film and food suggestions, links, and an article written by yours truly. If you happen to be new here, there’s a whole 97 other issues you can explore here!

Whether you become a paid subscriber or not, I’m very grateful to each of you who read and respond to this newsletter.

PSA: This email is LONG and due to some obscure technical reasons on Gmail it gets ‘clipped’, which means you are not seeing the whole thing.

You can see at the bottom of the email if it says “message clipped”, then click “View entire message” to see it all.

You are not getting it all if you don’t see my signature at the bottom.Alternatively, if you don’t want to read this in your email, you can use the Substack app (where you can listen to the article read out) or read it online at LectioLetter.com

Status Board

Life

This month I had planned a slight uptick in my writing cacapity which was summarily squashed by a few events seen and unforeseen. The most dramatic was Rachel getting quite sick with food poisoning. So severe that in normal circumstances she may have ended up in hospital, but our local doctor was able to ‘rig up’ an IV and get her recovering.

Rachel was sick over our 17th Wedding Anniversary, we lived out our “in sickness and in health” vows with some chicken soup and some flowers.

It didn’t hold up back from reminiscing over the last 17 years, which all in all have been very good to us both. Here’s one of our favourite photos of us (looking like children!) at our wedding ceilidh (traditional Scottish dance party).

Rachel was thankfully back on her feet within a week or so and I went to teach in a YWAM DTS on the Character and Nature of God. It was an enjoyable week, helping young enthusiastic Christians in their 20’s who were starting out in missions. They were a bright bunch and my favourite moment is always the “Question and Response” times.

Despite being engaged in the core areas I was teaching, the questions (as was invited) were broad; bringing up stick theological issues like;

Once saved always saved?

Can women be pastors?

Could we fall again after Jesus comes back?

Do we really have free will?

Which made things easy, because all the answers are “Yes” (For those who can’t hear my tone of voice, that is (kind of) a joke).

But I realise the older I get, my felt need is less to untie the ‘big’ abstract philosophical questions, but to root big realities in the specifics of my everyday life. The “big” theological questions can too often be strategies of avoidance in my experience.

In this last week, we’ve been joined by Rachels family and were able to take a trip back to our beloved Tulbagh valley which is about 2 hours away from our home here in Cape Town.

Reading

Yesterday I looked through the oft-quoted The Next Evangelicalism: Freeing the Church from Western Cultural Captivity by Soong Chan Rah.

His introduction unpacks his indebtedness to US white evangelicalism and he goes on to critique the individualism and materialism that has infected evangelicalism and leaves us culturally bound.

This critique is on point and he unpacks why mega church and the now defunct “emergent” church is simply a continuation of this pragmatic indiviudualism. He goes on to present a salve in the form of learning from non-western immigrant churches in humility for what we have lost. I am sympathetic to this suggestion and have argued myself for a greater cultural humility in mission.

It is essentially a cultural version of Richard Foster’s Stream of living water, where disparate fragmented aspects of the Jesus way need to be reunited. The critique alone would serve most leaders who struggled to diagnose their consistently mono-cultural church environments but I am less assured that the salve will heal us fully.

I am concerned that since the writing of the book (2013, I think), there is increased cross-cultural hostility and distrust especially in the US as simple requests for humble learning from other perspective gets crushed as ‘woke’ but I am also less naive that ‘exposure and humility’ will reunite an increasingly polarised church.

Finally, Rah’s North American context inevitably overwhelms the books references and part of what the church will wrestle with (as you can see in the recent GAFCON split) is the global church, not just the church in North America. We are increasingly unintelligible to one another and bridge building will be the work of serious spiritual warfare.

Other than that there’s not been much time to read in the last few weeks, but instead I’d thought I’d share some reviews of books that I’d like to read soon!

Liturgical Mission by Winfield Bevins

I’ve actually begun this book already and so far it is eminently readable and I’m looking forward to getting to the chapters in the second half as the beginning is something of a a reappraisal of Robert Webber for the 21st century liturgical renewal.

Mission, therefore, is central to who we are as Christians and what we are called to do as the church and body of Christ. According to missiologist Ed Smither, “Mission has been central to the identity of the Christian movement since its inception—Christianity is a missionary faith.” We are called to participate in God’s holistic mission in word (evangelism, making disciples), deed (caring for human needs, bringing justice, and seeking reconciliation), and stewardship of the earth (creation care).

Rather than seeing mission as something the church does apart from its liturgy, we must realize that mission begins in worship. Orthodox theologian Alexander Schmemann encourages us to understand that mission flows from the liturgical and sacramental life of the church, “for it alone makes possible the liturgy of mission.” His phrase “the liturgy of mission” is a reminder that liturgy should always lead to the sending activity of the church. Both worship and mission are at the very heart of the church’s calling.

A Review here

Living in Union with Christ: Paul’s Gospel and Christian Moral Identity by Grant Macaskill

Macaskill wrote that the “core claim of this book is that all talk of Christian moral life must begin and end with Paul’s statement, ‘It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me’ (Gal 2:20), and must understand the work of the Holy Spirit rightly in relation to Christ’s presence” (p. 1). Macaskill explained this claim to mean “that we can never talk about the moral activity of a Christian without always, in the same breath, talking about Jesus, because the goal of our salvation is not that we become morally better versions of ourselves but that we come to inhabit and to manifest his moral identity” (p. 1) (emphasis original). Thus, as Macaskill would later note, the sinner’s need for “an alien righteousness” extends beyond justification to include sanctification as well. We need the righteousness of Christ to “inhabit our limbs, lips, and neuron if we are to live and think in a way that honors God, if we are to confess him rightly” (p. 3).

A Review here

Listening

Parcels has continued to be in our heavy rotation

Rachel has been enjoying this song from Cageless Birds and I used it in a response time with the DTS

Our nieces have been singing and playing Olivia Deans new album which has some catchy tunes

London based Jazz artist Alfa Mist just released a new album and this title track from his album is great

The Work we Worship that makes us Slaves

Our modern world is built on work. Work is how wealth is made and how we define success. It’s the primary identity marker we ask for upon meeting someone, and the way we name ambition and direction for our own lives by seeking a career path.

Work, of course, was part of God’s intention for human beings from the very beginning. The first humans were given the command to work and keep creation on behalf of, and in relationship with, the Creator.

The failure of God’s first partners in creation was not merely a moral rule-break, but a failure to do the work God had given. The humans God created were made to act on His behalf — ruling, subduing, and stewarding the creatures they had named. Yet in the end, they were ruled and subdued by the craftiest of creatures, the serpent, who invited them to become like gods themselves.

The implications of this failure were the distortion of every good thing God had given. In Genesis 3:16-19, we discover the goods of human life would become diseased; their work, their relationships with God and one another, along with their call to steward the earth and fill it through childbearing — all became troubled instead of the gift they were always meant to be.

The Long Labor of Redemption

In the labour of God to redeem humanity as His partners, God eventually draws near to the family of Abram. Their simple response of trust in God’s call to redeem their own lives and their hope for children changed both their lives and their names. A people born from their blessing would, in turn, be a blessing for all peoples and all creation, just as those first humans were made to be.

Through the twists and turns of Abraham’s descendants — forgetful of their call and instead jealous of surrounding people — they became a blessed bloodline caught in the vice of Egypt’s cursed and work-crazed world.

Four hundred years of slavery ensued as God’s promise gestated in their suffering songs, as they cried out to Yahweh for deliverance. The ancients knew well the forty weeks of gestation required for human life to come to full term, and those four hundred years — and the forty years that followed in the wilderness — were as pregnant as Sarah’s womb that initiated God’s redemption plan.

A Baby in a Basket

This chapter of the story begins again with another baby — Moses — cast out into a makeshift ark upon the Nile, carried by God’s redemption just as Noah and his family had been before, straight into the arms of the serpent-king Pharaoh’s household. Moses grows older and gains God’s heart for the redemption of His people as he sees their suffering. Yet he acts in his own strength and anger, killing an Egyptian slave master.

Like his Edenic forebears, he reaches to accomplish the very deliverance in the heart of God through means, timing, and ways far from God. As he escapes into the wilderness, foreshadowing the journey he would lead his people in later, he is humbled by his transition from a palace to a life herding sheep. He is drawn once again — turning aside to a burning bush — and hears the call to announce to Pharaoh: “Let my people go, so that they may worship me.”

Work — meant to be the blessing of a relational partnership with God, to bring forth beauty, order, and abundance as a living revelation of God’s character — has devolved into the hell-pit of Egyptian slavery. No rest. No freedom. Work poisoned to its very core.

Rest Before Work

But it is rest and not work that humans are most foundationally made for. As we turn the pages back from Exodus to Genesis, we see that God exuberantly creates the world in six days, and on the sixth day, the image-bearers — the first humans — are made. On the seventh day, the inaugural Sabbath commences.

Consider this for a moment; The first full day of human life is spent sharing in the rest of all that God had done.

From that place of resting in God’s accomplishments, the humans were then led into their own vocations — but not before recognizing that all their work was simply response and participation in the greater work that only God could do, and had done.

Many centuries later — though many centuries before us — an African, half-Berber bishop named Augustine penned words opening his world-famous autobiography, the Confessions, which have resonated with countless human hearts in the centuries that have followed:

“You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they finds their rest in you.”

— Augustine

Restless Hearts and Working Hands

We were made for rest. But our sin-confused relationship with work always obscures the deeper call of relationship with God. As we ignore God’s invitation to know Him — in the wonder and glory of all He has done and all that He is — our relationship to what we do and where we do it cannot help but become deeply disordered.

We find ourselves yearning for a clear sense of who we are, whose we are, and where we are — and we do this by taking the temperature of our work and its connected successes or failures. We end up searching for orientation outside of God, frantically drawing our sense of worth from what we do, what we have, or what we have accomplished — or not.

While most of us don’t have a literal Pharaoh cracking a serpentine whip demanding our slavery, we nonetheless act as slaves — giving our everything to the accomplishment of work for the sake of gaining our worth. But on that first day of the original humans’ lives — before work — they were immersed in the Sabbath delight of God’s accomplishments. Their worth to God was clear. He didn’t need them; He wanted them.

Remember the Rest

Returning to the Exodus story, we see Moses leading God’s people out of slavery, and into that fray flies the wisdom and redemption of God: to institute a Sabbath remembrance at the heart of His commandments. Like a rehabilitation program for a people flogged to an inch of their lives, the commandments offer a renewed way of being in the world — a reshaping of their souls and sense of self.

The earliest reflections on these commands — which became central to the identity of Abraham’s people — noted that the Sabbath commandment begins differently from all the others. While the familiar rhythm of most commands begins, “You shall not…,” this one begins, “Remember.”

Maybe this points to humanity’s disordered relationship with work — that we are called to remember something we are so prone to forget. But certainly it is to remember that, from the very beginning of His story, God is not looking for obedient worker bees, but for partners and friends.

The Easy Yoke

During Jesus’ earthly ministry he condemned the corruption of the Sabbath practice — seeing that the very rhythm meant to remind people of their value before their work had instead become an unbearable burden. He instead tells those that follow Him, the Exodus Yahweh in the flesh;

“Take my yoke upon you and learn from me, for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls”

— Jesus in Matthew 11:28-30

Jesus confronted a practise that was meant to re-story Abraham’s family line as they remembered they were freed from slavery back into partnership with God. He did not intend to abolish it.

Near the end of His life, in the Gospel of John, He tells His followers, “I no longer call you slaves, but friends.” Finally, as he heads to jerusalem to fulfill his earthly mission culminating in giving His life on a cross he arrives during the passover. The festival at which Abraham’s people remembered they had been freed from slavery. His bodily resurrection was the final promise that YHWH would deliver us from the slavery of the fear of death into the sabbath rest of his rule and reign.

A weekly sabbath practised by Abraham’s people until today can seem impossible to modern Christians. We live in a hyper connected age when creating any distance from work and productivity through an intentional sabbath practise seems like a fantasy. The challenge is made even harder in our instantaneous society by the fact that Sabbath doesn’t “work” as a one-off but only in cumulative, continuous practise.

With that being said, as Travis West notes in his book “The Sabbath Way”, learning to live in Sabbath has to grow to maturity through the inevitable ‘adolescence’ of imperfect attempts.

The point is to keep going, to trust the slow quiet work of God’s Spirit reminding us that work is good but we were made for the rest of loving relationship first. If we can allow the Spirit of God to work through the consistent, even while faltering, practise of Sabbath rest, we might be rehabilitated from slavery into the kingdom of the beloved son.

Living increasingly in the light of that Kingdom would remind us that, as Henri Nouwen said;

“We are not what we do, we are not what we have, we are not what others think of us. Coming home is claiming the truth. We are the beloved children of a loving creator.”

Miscellaneous Links

Paul and the Language of Faith

Nijay Gupta, NT Scholar at Northern has been doing a retrospective summarising his books. This summary of his Paul and the language of Faith, is a good primer for anyone who has a non-academic interest in picking up how academic reflections on the context of the use of the word faith and how it isn’t just, as Mark Twain once quipped “Having faith is believing in something you just know ain’t true.”

“…non-Jewish Greek texts as well as Jewish texts the term pistis (often translated “faith”) had a wide range of meaning, including cognitive processing (belief), embodied loyalty (allegiance), and the operation of the will (trust). Commentaries rarely took this into consideration.”

I only got 5 minutes into this 50+ min documentary about the set up of one of the logistics locations for Antarctica but it’s the type of documentary that sucks me in… Now I just have to find uninterrupted time to enjoy this Anderson-esque film;

I’ve been very intrigued about Paul Kingsnorth’s perspective and He was recently interviewed by Russell Moore about how AI is demonic! I imagine many of you’d find interesting. Kingnorth’s own journey to Christianity, connection to nature, and recognition of the de-humanising forces at work in our world is worth ‘salting’ our own engagement in the increasingly technologically dominated reality we live alongside.

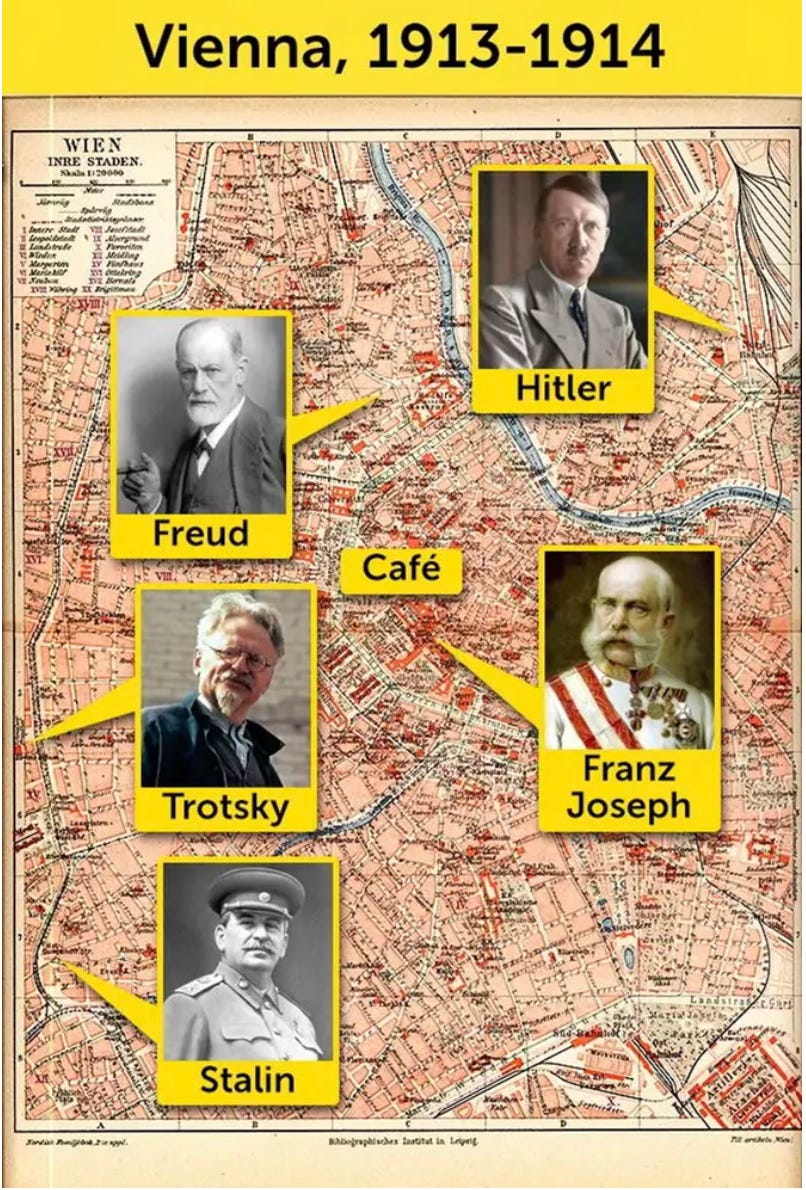

Yupp, all these historical figures that had such a lasting impact on the 20th Century (and beyond) lived in the City of Vienna at the same time during 1913-1914. The idea that Stalin could have, with real probability, walked past a homeless Hitler trying to sell his mediocre watercolor paintings on the street is an interesting one to consider.

from Earthly Mission

Finally, I’ve been thinking about how we approach what we call theology for a long time. I’m convinced that the enlightenment rationality approach leaves us with a broken set of pieces that are fragments of God who is, by the earliest Judeo-Christian confession “One”. What I like about Brad Jersey’s response to a question about his approach to theology is the integration of encounter. Inter-personal encounters with the God we come to know fully in Jesus are the bed rock of the biblical narrative. We lose something crucial when theology is done in such a way that the significance of personal encounter is lost and yet we can’t simply extrapolate up from our experiences. We must come to know them in the context of a story that, yes includes our own lives, the life of the Church in our time, but also in the context of a story that existed far before us and will continue beyond us.